Provided by the Information Sharing Workgroup

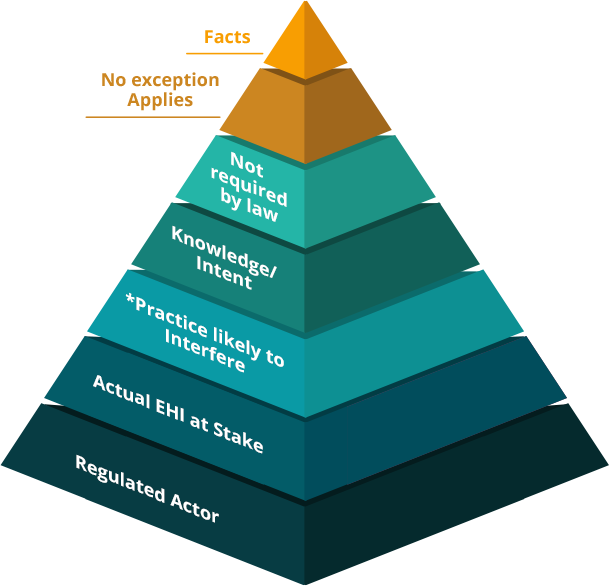

Information blocking is a (1) practice conducted by an (2) actor that is (3) not required by law or (4) covered by an applicable exception that is (5) likely to interfere with (6) access, exchange, or use of (7) EHI and that

Assessing whether a practice is information blocking turns on the individual facts and circumstances, including intent and whether the practice satisfies an exception. Not meeting an exception does not mean the actor is information blocking.

1 See 42 U.S.C. § 300jj-52(a)(1) (statutory definition of “information blocking”); 45 C.F.R. § 171.103 (regulatory definition of “information blocking”).

2 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program, 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,642, 25,808 (May 1, 2020).

The Cures Act and regulatory preamble provide illustrative examples of practices that may be likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use. 3

Ultimately, whether a practice will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to assess whether it rises to the level of an interference given the specific facts and circumstances at issue. 4

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,809 (emphasis added).

2 Id. (“We noted that whether the risk of interference is reasonably foreseeable will depend on the particular facts and circumstances attending the practice or practices at issue. Because of the number and diversity of potential practices, and the fact that different practices will present varying risks of interfering with access, exchange, or use of EHI, we did not attempt to anticipate all of the potential ways in which the information blocking provision could be implicated. Nevertheless, to assist with compliance, we clarified certain circumstances in which, based on our experience, a practice will almost always be likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of EHI. We cautioned that the situations listed are not exhaustive and that other circumstances may also give rise to a very high likelihood of interference under the information blocking provision. We noted that in each case, the totality of the circumstances should be evaluated as to whether a practice is likely to constitute information blocking.”).

3 See 42 U.S.C. § 300jj-52(a)(2) (Information blocking practices “may include (A) practices that restrict authorized access, exchange, or use under applicable State or Federal law of such information for treatment and other permitted purposes under such applicable law, including transitions between certified health information technologies; (B) implementing health information technology in nonstandard ways that are likely to substantially increase the complexity or burden of accessing, exchanging, or using electronic health information; and (C) implementing health information technology in ways that are likely to- (i) restrict the access, exchange, or use of electronic health information with respect to exporting complete information sets or in transitioning between health information technology systems; or (ii) lead to fraud, waste, or abuse, or impede innovations and advancements in health information access, exchange, and use, including care delivery enabled by health information technology.”); see also 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,809, 25,811-18.

4 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,649 (“[F]ailure to meet the conditions of an exception does not automatically mean a practice constitutes information blocking. A practice failing to meet all conditions of an exception only means that the practice would not have guaranteed protection from CMPs or appropriate disincentives. The practice would instead be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to assess the specific facts and circumstances (e.g., whether the practice would be considered to rise to the level of an interference, and whether the actor acted with the requisite intent) to determine whether information blocking has occurred.”)

A provider violates the information blocking rules only when such actor “knows [a] practice is unreasonable and is likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.” 1

The information blocking rules do not define “knows” or “unreasonable.”

However, in proposed rulemaking, HHS acknowledged that the intent standard is different for providers than it is for developers, HINs and HIEs, and suggested that it understood the word “knows” to refer to “actual knowledge.” 2

2 21st Century Cures Act: Establishment of Disincentives for Health Care Providers That Have Committed Information Blocking, Proposed Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. 74,947, 74,951-52 (Nov. 11, 2023) (“The different intent standard for information blocking by a health care provider is why OIG does not expect to use ‘actual knowledge’ as an enforcement priority [for providers]. OIG has significant experience and expertise investigating and determining whether to take an enforcement action based on other laws that are intent-based (for example, the Federal anti-kickback statute, and Civil Monetary Penalties Law, 42 U.S.C. 1320a–7b(b) and 1320a–7a). This history will inform the use of OIG’s discretion to investigate health care providers that OIG believes may have the requisite intent.”).

*ASTP/ONC has emphasized that Information Blocking can occur even without a request, such as through a practice related to contract terms or a failure to meet reporting requirements. See this FAQ

Block 1

Practice

Block 2

Actor

Block 3

Not Required by Law

Block 4

Covered by an Applicable Exception

Block 5

Likely to Interfere

1 45 C.F.R. § 171.102; see also 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,819 (emphasizing that a practice need only be a single act or omission).

An “actor,” for purposes of the information blocking regulations, is a health care provider, health IT developer of certified health IT, health information network or health information exchange. 1

An individual or entity is acting as a “health care provider” if it is engaging in a practice related to its role as one of the following: 2

An individual or entity is acting as a “health IT developer or certified health IT” if it is engaging in a practice related to it developing or offering health IT11 (other than self-developing health IT not offered to others), and if it has one or more certified Health IT Modules when it engages in the practice. 12

An individual or entity is acting as a “health information network or health information exchange” if it is engaging in a practice related to its ability to determine, control or have the discretion to administer any requirement, policy, or agreement that permits, enables, or requires the use of any technology or services for access, exchange, or use of EHI for treatment, payment, or health care operations 13 among more than two unaffiliated individuals or entities (other than itself) that are enabled to exchange with each other. 14

1 See 45 C.F.R. § 171.102.

2 See id.; 42 U.S.C. § 300jj-52.

3 As defined at 42 U.S.C. § 300x-2(b)(1).

4 As defined at id. § 1395l(i).

5 As defined at id. § 1395x(r).

6 As defined at id. § 1395u(b)(18)(C).

7 As defined at 25 U.S.C. § 5301 et seq.

8 As defined at id. § 1603.

9 As defined at 42 U.S.C. § 256b(a)(4).

10 As defined at id. § 1395w–4(k)(3)(B)(iii).

11 As defined at id. § 300jj(5)).

12 See 45 C.F.R. § 171.102.

13 As defined at id. § 164.501 (regardless of whether the individual or entity is a HIPAA covered entity).

An actor is not information blocking when engaging in a practice required by law, or when declining to engage in a practice that is prohibited by law. 1

This includes practices that are required or prohibited by federal, state, and tribal statutes (including HIPAA), regulations, court orders, and binding administrative decisions or settlements. 2

1 See 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,794, 25,845-46.

2 See id.

There are currently 9 exceptions that pertain to responding to requests to access, exchange, or use EHI under the information blocking rules:

Exceptions That Involve Not Fulfilling Requests

Exceptions That Involve Procedures for Fulfilling Requests

Exceptions Related to Participation in TEFCA

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,649 (“[F]ailure to meet the conditions of an exception does not automatically mean a practice constitutes information blocking. A practice failing to meet all conditions of an exception only means that the practice would not have guaranteed protection from CMPs or appropriate disincentives. The practice would instead be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to assess the specific facts and circumstances (e.g., whether the practice would be considered to rise to the level of an interference, and whether the actor acted with the requisite intent) to determine whether information blocking has occurred.”)

The Cures Act and regulatory preamble provide illustrative examples of practices that may be likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use. 3

Ultimately, whether a practice will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to assess whether it rises to the level of an interference given the specific facts and circumstances at issue. 4

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,809 (emphasis added).

2 Id. (“We noted that whether the risk of interference is reasonably foreseeable will depend on the particular facts and circumstances attending the practice or practices at issue. Because of the number and diversity of potential practices, and the fact that different practices will present varying risks of interfering with access, exchange, or use of EHI, we did not attempt to anticipate all of the potential ways in which the information blocking provision could be implicated. Nevertheless, to assist with compliance, we clarified certain circumstances in which, based on our experience, a practice will almost always be likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of EHI. We cautioned that the situations listed are not exhaustive and that other circumstances may also give rise to a very high likelihood of interference under the information blocking provision. We noted that in each case, the totality of the circumstances should be evaluated as to whether a practice is likely to constitute information blocking.”).

3 See 42 U.S.C. § 300jj-52(a)(2) (Information blocking practices “may include (A) practices that restrict authorized access, exchange, or use under applicable State or Federal law of such information for treatment and other permitted purposes under such applicable law, including transitions between certified health information technologies; (B) implementing health information technology in nonstandard ways that are likely to substantially increase the complexity or burden of accessing, exchanging, or using electronic health information; and (C) implementing health information technology in ways that are likely to- (i) restrict the access, exchange, or use of electronic health information with respect to exporting complete information sets or in transitioning between health information technology systems; or (ii) lead to fraud, waste, or abuse, or impede innovations and advancements in health information access, exchange, and use, including care delivery enabled by health information technology.”); see also 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,809, 25,811-18.

4 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,649 (“[F]ailure to meet the conditions of an exception does not automatically mean a practice constitutes information blocking. A practice failing to meet all conditions of an exception only means that the practice would not have guaranteed protection from CMPs or appropriate disincentives. The practice would instead be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to assess the specific facts and circumstances (e.g., whether the practice would be considered to rise to the level of an interference, and whether the actor acted with the requisite intent) to determine whether information blocking has occurred.”)

Block 6

Access, Exchange, or Use

Block 7

Electronic Health Information (EHI)

Block 8

Knows, or Should Know

Block 9

Knows

“Access” is defined as “the ability or means necessary to make [EHI] available for exchange or use.” 1

“Exchange” is defined as “the ability for electronic health information to be transmitted between and among different technologies, systems, platforms, or networks.” 2

“Use” is defined as “the ability for [EHI], once accessed or exchanged, to be understood and acted upon.” 3

EHI, for purposes of information blocking, includes electronic protected health information that would be included in a designated record set (as defined by HIPAA), regardless of whether they are maintained by or for a covered entity. 1

For instance, data such as audit trails, credentialing records, lists of prices/charges, and other information not linked to an identifiable patient (such as OR scheduling information) likely would not fall into this definition of EHI.

Each organization should consider adopting its own policies and procedures for assessing what information constitutes EHI.

The information blocking rules do not define “knows, or should know.”

However, the statute governing civil monetary penalties, which gives OIG authority to impose penalties for information blocking,1 defines “should know” to mean, in relevant part, that a person “acts in deliberate ignorance of the truth or falsity of the information” or “acts in reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of the information.” 2

1 See Grants, Contracts, and Other Agreements: Fraud and Abuse; Information Blocking; Office of Inspector General’s Civil Money Penalty Rules, 88 Fed. Reg. 42,820, 42,820 (Jul. 3, 2023).

A provider violates the information blocking rules only when such actor “knows [a] practice is unreasonable and is likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.” 1

The information blocking rules do not define “knows” or “unreasonable.”

However, in proposed rulemaking, HHS acknowledged that the intent standard is different for providers than it is for developers, HINs and HIEs, and suggested that it understood the word “knows” to refer to “actual knowledge.” 2

2 21st Century Cures Act: Establishment of Disincentives for Health Care Providers That Have Committed Information Blocking, Proposed Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. 74,947, 74,951-52 (Nov. 11, 2023) (“The different intent standard for information blocking by a health care provider is why OIG does not expect to use ‘actual knowledge’ as an enforcement priority [for providers]. OIG has significant experience and expertise investigating and determining whether to take an enforcement action based on other laws that are intent-based (for example, the Federal anti-kickback statute, and Civil Monetary Penalties Law, 42 U.S.C. 1320a–7b(b) and 1320a–7a). This history will inform the use of OIG’s discretion to investigate health care providers that OIG believes may have the requisite intent.”).

Information blocking is not implicated.

Evaluate the individual facts and circumstances, including whether another exception applies

Manner Exception applies.

The information blocking process is split into four parts which include:

Are you an actor under the information blocking regulations?

An “actor,” for purposes of the information blocking regulations, is a health care provider, health IT developer of certified health IT, health information network or health information exchange. 1

An individual or entity is acting as a “health care provider” if it is engaging in a practice related to its role as one of the following: 2

An individual or entity is acting as a “health IT developer or certified health IT” if it is engaging in a practice related to it developing or offering health IT11 (other than self-developing health IT not offered to others), and if it has one or more certified Health IT Modules when it engages in the practice. 12

An individual or entity is acting as a “health information network or health information exchange” if it is engaging in a practice related to its ability to determine, control or have the discretion to administer any requirement, policy, or agreement that permits, enables, or requires the use of any technology or services for access, exchange, or use of EHI for treatment, payment, or health care operations 13 among more than two unaffiliated individuals or entities (other than itself) that are enabled to exchange with each other. 14

1 See 45 C.F.R. § 171.102.

2 See id.; 42 U.S.C. § 300jj-52.

3 As defined at 42 U.S.C. § 300x-2(b)(1).

4 As defined at id. § 1395l(i).

5 As defined at id. § 1395x(r).

6 As defined at id. § 1395u(b)(18)(C).

7 As defined at 25 U.S.C. § 5301 et seq.

8 As defined at id. § 1603.

9 As defined at 42 U.S.C. § 256b(a)(4).

10 As defined at id. § 1395w–4(k)(3)(B)(iii).

11 As defined at id. § 300jj(5)).

12 See 45 C.F.R. § 171.102.

13 As defined at id. § 164.501 (regardless of whether the individual or entity is a HIPAA covered entity).

Has the actor received a actionable request to access, exchange, or use EHI?

In order for an actor to respond to the request in an appropriate and timely manner, a request should contain enough information to allow an actor to answer certain basic threshold questions. Such questions include: 1

1 The information blocking rules do not define what constitutes a “request” for access, exchange, or use of EHI. As discussed herein, the Preambles to the information blocking regulations provide guidance as to what types of practices related to inquiries from requestors would not be likely to interfere with access, exchange, or use of EHI. We incorporate these in a definition of “cognizable request.”

2 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program, 85 Fed. Reg. 25,642, 25,892 (May 1, 2020) (“[A]n essential element of the information blocking provision is that there is actual EHI at stake.”). The definition of EHI only includes electronic protected health information to the extent it would be included in a designated record set; this does not include hypothetical or future EHI. 45 C.F.R. § 171.102; see also 45 C.F.R. § 160.103.

3 See 45 C.F.R. § 171.102 (defining “interoperability element” as technology that “[m]ay be necessary to access, exchange, or use [EHI]” (emphasis added)); 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,814 (“[I]f there is no nexus between a requestor’s need to license an interoperability element and existing EHI, an actor’s refusal to license the interoperability element altogether or in accordance with § 171.303 would not constitute an interference under the information blocking provision.”) (emphasis added); id. at 25,889 (“In order for an actor to consider licensing its interoperability elements . . . the requestor would need to have a claim to the underlying, existing EHI for which the interoperability element would be necessary for access, exchange, or use[.]”).

4 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,814 (“[I]f there is no nexus between a requestor’s need to license an interoperability element and existing EHI, an actor’s refusal to license the interoperability element altogether or in accordance with § 171.303 would not constitute an interference under the information blocking provision.”) (emphasis added); id. at 25,889 (“For example, if a developer of certified health IT included proprietary APIs in its product to support referral management, it would not need to license the interoperability element(s) associated with those referral management APIs simply because a requestor ‘knocked on the actor’s door’ and asked for a license with no EHI involved. The license request from a requestor must always be based on a need to access, exchange, or use EHI at the time the request is made— not on the requestor’s prospective intent to access, exchange, or use EHI at some point in the future.”) (emphasis in original).

“Access” is defined as “the ability or means necessary to make [EHI] available for exchange or use.” 1

“Exchange” is defined as “the ability for electronic health information to be transmitted between and among different technologies, systems, platforms, or networks.” 2

“Use” is defined as “the ability for [EHI], once accessed or exchanged, to be understood and acted upon.” 3

Is the actor prohibited by law from responding or required by law to respond in this way?

An actor is not information blocking when engaging in a practice required by law, or when declining to engage in a practice that is prohibited by law. 1

This includes practices that are required or prohibited by federal, state, and tribal statutes (including HIPAA), regulations, court orders, and binding administrative decisions or settlements. 2

1 See 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,794, 25,845-46.

2 See id.

The request does not trigger obligations under the information blocking rules.

Not every request implicates the information blocking rules; only requests that could be necessary to access, exchange, or use existing EHI (“actionable requests”). For example, a request to develop new software features or interpretive tools, or a request for non-EHI data like audit logs don’t implicate information blocking.

Consider using and publicizing a standard pathway to receive requests (e.g., an intake form, web portals, dedicated email account). Train your organization to route all requests to that process. A request shouldn’t be deemed actionable unless the requestor has given you enough information to evaluate the request and take action on it.

Can you reach agreeable terms with the requestor to provide access, exchange, or use of EHI?

Terms reached pursuant to the manner requested condition of the Manner Exception need not satisfy the Licensing or Fees Exceptions. 1

These terms can be “whatever terms the actor chooses” and any royalties or fees can be charged at the “market” rate. 2

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,877 (“If an actor fulfills a request described in the content condition in any manner requested: (1) Any fees charged by the actor in relation to its response are not required to satisfy the Fees Exception in § 171.302; and (2) any license of interoperability elements granted by the actor in relation to fulfilling the request is not required to satisfy the Licensing Exception in § 171.303 (§ 171.301(b)(1)(ii)).”).

2 Id.

Have you offered to fulfill the request in one or more alternative manners?

The Manner Exception sets forth a list of alternatives that satisfy the Exception, in the following order: technology certified to ONC standards, industry-standard technology, and machine-readable format. While the text of the exception suggests that this list operates according to “order of priority” and that a requestor must “specify” certified or industry-standard technology1, later regulatory changes and subregulatory guidance indicate that this exception is not intended to operate as rigidly as drafted. With regard to proceeding in “order of priority,” the preambular discussion in HTI-1 suggests that what is important to ONC is that at least one standards-based technology is offered—whether it is certified or industry-standard technology. 2 With regard the language to “specifying” technology, the preamble further acknowledges that the Exception is met when an actor offers and a requestor agrees to an alternative manner. 3

The information blocking rules and subregulatory guidance do not prescribe how “close” an offered alternative has to be to the manner requested. An alternative manner may not actually provide the access, exchange, or use of EHI the requestor was originally requesting, though ONC anticipates that a requestor would reject the alternative in this instance. 4

With respect to requests for licensing technology, actors who do not want to license are not required to do so if they are able to respond in an alternative manner. 5

2 89 Fed. Reg. at 1,383 (explaining, in discussing the manner exception exhausted condition of the Infeasibility Exception, that its policy goal is to ensure that “interoperable, standards-based exchange remains favored over other methods of exchange” and acknowledging the problem of the “unequal burden on actors who are not required by other government regulations or incentivized by any public or private program to use certified health IT”).

3 Id. at 1,393 (“In the Manner Exception, one policy objective is to ensure the requestor receives the EHI in either the manner requested or in an alternative manner to which the requestor agrees. This policy assumes that the requestor would not agree to an alternative manner unless that manner allowed them the access, exchange, or use of EHI which they sought in the first place.”)

4 Id. (noting that the Manner Exception “assumes that the requestor would not agree to an alternative manner unless that manner allowed them the access, exchange, or use of EHI which they sought in the first place”).

Did the requestor agree to an alternative manners?

3 Nothing in the information blocking rules or subregulatory guidance suggests that it would be inappropriate to simply treat this as a new “request” for purposes of the Manner Exception.

The Manner Exception applies.

Look at the facts and circumstances, consider other exceptions.

Use a catalog or menu of your “manner requested“ product offerings, your terms, fees, and conditions for them.

Develop a list or catalog of readily-available alternatives (if feasible, certified HIT or industry standard technology). Take into account the Licensing and/or Fees Exceptions.

An agreement can be inferred. After offering alternatives, actors commonly don’t often hear back from the requestor. Actors should consider adopting a process for deeming requests closed after offering alternative manners.

Does the actor charge a royalty for the technology?

Neither the term “royalty” nor the term “fee” is defined in the information blocking rules, and the preambles provide little additional insight into the distinctions between these terms.

In the IP space, the term “royalty” is sometimes, but not always, used to refer to ongoing usage-based payments for IP, while the term “fee” is sometimes, but not always, used to refer to an upfront payment for IP.

Evaluate facts and circumstances, including whether another exception may apply.

Offer a license within 10 business days from receipt of the actionable request, and complete negotiations within 30 business days.

If the actor is licensing technology as an alternative manner, an actor should decide whether the amount charged is a royalty, is a fee, or includes both.

Objective and verifiable criteria for determining license terms cannot be based on the actor’s “subjective judgment or discretion.” However, these differences may be based on, for example, “actual differences in the costs that the actor incurred or other reasonable and non-discriminatory criteria.” 1

Actors are not required to apply the same terms for everyone requesting a license. Actors have discretion to allocate costs differently for different classes of customers. 1

1 In the context of the Licensing Exception, ONC wrote in preamble that this requirement “does not mean that the actor must apply the same terms for all persons or classes of persons requesting a license” and that “any differences in terms would have to be based on actual differences in the costs that the actor incurred or other reasonable and non-discriminatory criteria.” 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,896. Discussing the uniform application of criteria to similarly situated classes in the context of the Fees Exception, ONC wrote in preamble that actors have “discretion to allocate costs differently for different classes of customers, while ensuring that any differences in cost allocation are based on actual differences in the class of customer. For instance, under this provision, fees must be reasonably allocated among all similarly situated large hospital systems (above a certain established size threshold) to whom a technology or service is supplied, or for whom the technology is supported. However, the allocation of fees for the same technology or service could be quite different for a small, non-profit, rural health clinic.” 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,883.

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,896 (“[T]he proposed condition would not preclude an actor from pursuing strategic partnerships, joint ventures, co-marketing agreements, cross-licensing agreements, and other similar types of commercial arrangements under which it provides more favorable terms than for other persons with whom it has a more arms-length relationship. We explained that in these instances, the actor should have no difficulty identifying substantial and verifiable efficiencies that demonstrate that any variations in its terms and conditions were based on objective and neutral criteria.”) (citing 84 Fed. Reg. at 7,548).

Note that terms and conditions may vary based on neutral and objectively verifiable criteria such as the resources required by certain types of apps and the risks associated with certain requests.1

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,896 (“The terms and conditions could vary based on neutral, objectively verifiable, and uniformly applied criteria. These might include, for example, significantly greater resources consumed by certain types of apps, such as those that export large volumes of data on a continuous basis, or the heightened risks associated with apps designed to ‘write’ data to the EHR database or to run natively within the EHR’s user interface.”).

Actors are not required to apply the same terms for everyone requesting a license. Actors should consider using standard sets of terms for similar types of requestors.

ONC has acknowledged that whether a royalty is “reasonable” is a fact-dependent inquiry. 1 ONC did identify some factors that may go into an evaluation of reasonableness, which are set forth in the list below:

2 Note that ONC included in the Proposed Rule, but ultimately removed, a requirement that IP be licensed on RAND terms. See id. at 25,892. As such, we have excluded references to RAND from this list as outdated.

3 ONC suggested this would take into account “only the contribution of the elements themselves and not of the enhanced interoperability that they enable.” Id. at 25,893.

4 ONC suggested this would also take into account “only the contribution of the elements themselves and not of the enhanced interoperability that they enable.” Id.

Is the actor charging fees connected to the access, exchange, or use of EHI?

A fee is excluded if it is1

If the actor has otherwise satisfied the Manner Exception, the actor has satisfied one or more information blocking exceptions.

Evaluate facts and circumstances, including whether another exception may apply.

If the actor has otherwise satisfied the Manner Exception, the actor has satisfied one or more information blocking exceptions.

Objective and verifiable criteria used to determine fees may not be “arbitrary or anti-competitive.” 1

Actors are not required to apply the same terms for everyone requesting a license. Actors have discretion to allocate costs differently for different classes of customers.

Differences in cost allocation must be based on actual difference in the class of customer. For example, large hospital systems above a certain established size threshold may be similarly situated and incur distinct fees from a small, non-profit, rural health clinic. 1

Differences in price terms need to be based on “actual differences the costs that the actor incurred or other reasonable and non-discriminatory criteria.” 1

An actor is required to “allocate its costs in accordance with criteria that are reasonable and between only those customers that either cause the costs to be incurred or benefit from the associated supply or support of the technology.” 2

1 85 Fed. Reg. at 25,896 (“[T]he proposed condition would not preclude an actor from pursuing strategic partnerships, joint ventures, co-marketing agreements, cross-licensing agreements, and other similar types of commercial arrangements under which it provides more favorable terms than for other persons with whom it has a more arms-length relationship. We explained that in these instances, the actor should have no difficulty identifying substantial and verifiable efficiencies that demonstrate that any variations in its terms and conditions were based on objective and neutral criteria.”) (citing 84 Fed. Reg. at 7,548).

The information sharing workgroup has a plethora of additional resources regarding information blocking. Visit the link below to access those resources.

Copyright © 2025 The Sequoia Project. All rights reserved.